I live in the far western suburbs of Chicago, we often mention that we moved here because you could still see the stars at night. While cities are amazing places buzzing with life, the open spaces of the farther suburbs (and the more affordable housing options) led us west. We were as surprised as anyone when the perfect home for us happened to be on a lot that was a big empty canvas with a very few trees and shrubs, and wide expanses of turf grass on what had not long ago been a farmer’s field.

I had gardened our lot in the city with the help of my parents, longtime gardeners themselves. We opted to decline the builder’s options when they finished that house, instead choosing to landscape the space ourselves. My parents brought small shrubs and plants from their local nursery and we eagerly dug them in, enjoying the process of going from a blank slate to a green wall of plants we had personally placed.

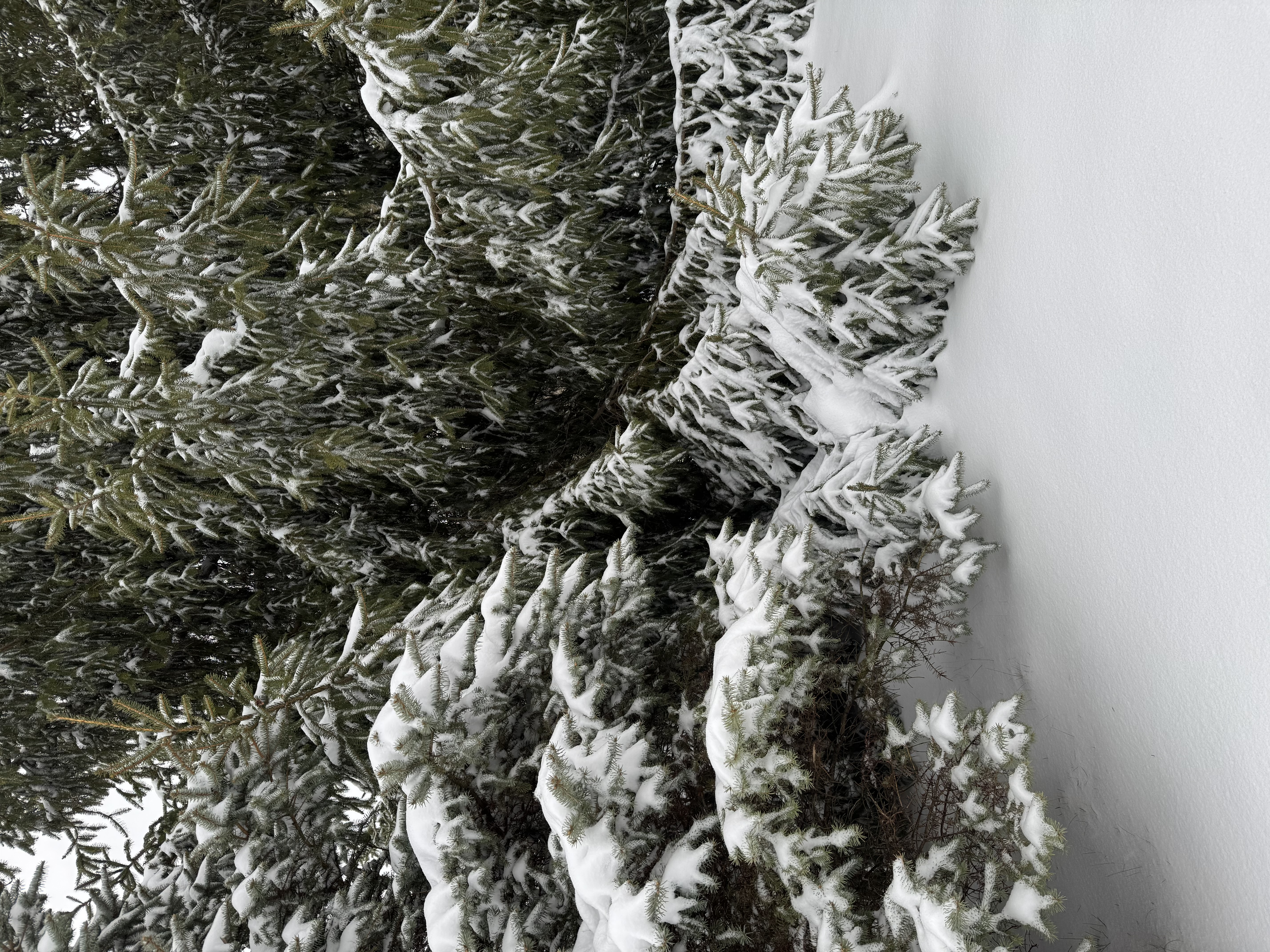

When it came time to figure out just what to do with our new much more giant suburban lot, we again engaged my parents in the process. My father took on a project manager role, one he was long accustomed to in his business consultant career. He helped organize the installation of trees that had been on order. The house sellers we bought from had planned to put in a number of trees but were transferred out of state suddenly. Their loss meant we gained by being able to send my dad to the tree farm where he thumped bark with his knuckles and picked red maples to line the driveway, a beautiful river birch to rest in the lowest/most prone to flooding part of the yard, majestic eastern white pines to crown one corner of the back, and a collection of small sized Norway spruces to anchor the other corner.

Not every choice lasted (rip, green ash trees that fell to the emerald ash borer 6 or 8 years later. Not many ash trees in the region survived that pest, and we all learned a valuable lesson in planting diverse groupings of trees, given what gaps the ashes left in the landscape that have only recently filled back in with new trees – one is a sprawling eastern red cedar that looks very much like it might one day lift its roots up out of the ground and begin marching around like a general directing its troops.) But my father has been gone a dozen years already, and most of those trees continue to reach for the skies.

Meanwhile, once we owned this place, we took seriously the responsibility to be stewards of this piece of land. Due to the codes and requirements of being in an unincorporated part of town, the lot is 1.25 acres, with a well and septic system dictating the minimum size. This gave us a large canvas, even considering the trees we installed before officially becoming suburbanites.

Not long after we moved here, we had a chance meeting with a wildflower gardener named Art Gara at a local home and garden show and it changed everything for us. He taught us about native plants, things that co-evolved with Illinois’ native bugs, butterflies, the birds and other beings that lived here. We already knew we were in a special place, throughout that first winter we saw deer silently step through the landscape at dusk. Very rarely we’d see a fox trotting through, looking for its next meal. Red-tailed hawks stood sentry on telephone poles and tall trees. We knew there was a circle of life to belong to. We didn’t know how central the plants would be to that circle until Art started teaching us.

He showed us what was coming up naturally in the ground, courtesy of a seed bank and a pattern of growing that the land knew, even if we humans had forgotten. Equisetum grew fluffy and wild through the front, some areas were well colonized by obedient plant (physostegia virginiana) – the pink blooms buzzing with bumblebees throughout the summer.

He suggested an upper section of native plants, and one lower where we had noticed occasional standing water or flowing water, our yard being part of the overall landscape that drains to our west. We didn’t think having standing water was a great idea even though the area in question was at significant distance from the house to not risk flooding, but the runoff struck us as less ideal. Art taught us about rain gardens, and planted a button bush, a few sedges and grasses, and cup plant which quickly decided it wanted to take over the place. Purple meadow rue bloomed early in the season, along with meadow anemone, followed by cup plant and gray-headed coneflower, buttonbush coming into bloom sometime in there despite the fact that every year I plan its funeral. Purple-flowering raspberry went in, so did New England aster and a few queen of the prairie.

Ahh the queen. My absolute favorite native plant.

In the drier spots, Art selected meadowsweet (spiraea alba) and purple coneflower, wild quinine and prairie dropseed, stiff goldenrod and more types of asters. Penstemon digitalis and more meadow anemone (who never met a patch of bare ground it didn’t want to colonize) filled in the spring blooming time. And we were soon off to the races, with native plants blooming throughout the growing season. Opportunistic friends arrived, too, like common violets, and daisy fleabane.

In the early years when our family was terrifically young, we hired Art and his crew to do the maintenance, which wasn’t constant, but it did require some regular tending to keep enthusiastic plants from being too enthusiastic, to remove invasives that come in with the wind, with the birds, and are in the dirt naturally. Every few years we’d ask Art and his team to add something more, to redo a portion of an existing planting bed with native plants, to extend an area, or, as the kids grew older, to take over spaces once reserved for their playset or soccer pitch with more native plantings.

Art died a number of years back and we have extended our own knowledge of native plants to continue to build upon his legacy. Now it’s part passion, part obsession, as I research specific plants to add that would do well in our yard, which tends toward sunny and dry though parts are becoming more shady as those trees grow. Recent discoveries include butterfly milkweed, all the huercheras, big and little bluestem, indiangrass, and new volunteers like cutleaf coneflower and late figwort. As I discover these “nobody planted this! where did it come from?” plants I realize that nature seems to know what it needs, the late figwort interplanting itself with other tall prairie plants like that cutleaf coneflower and a giant Joe pye weed. Tall beckons to tall.

Much of the work of the native plant gardener with a mature garden is in watching and learning from the plants themselves. I periodically go in and rejuvenate a section that seems to have gotten scraggly or over-dominated with one particular plant. I also learn about late figwort and harvest seeds to pass along to other native gardeners who prize this strange plant with the tiny orange flowers that draws pollinators like it’s their own personal ice cream truck, home on the range tinkling tinnily out of its imaginary speakers.

And so I learn about the garden and the garden teaches me. Between us, we figure out the right balance. And in that balance I find peace, quiet, and the remarkable marvel of a tiny bloom on the stout blue-eyed grass, the caterpillars of monarch and swallowtail butterflies, the native bumblebees that are flower specialists like the common easterns that adore New England aster.

Hummingbirds find cardinal flower, goldfinches hammer their small beaks against the seeds of cup plant, and squirrels make their nests high up in the canopy of red maples. Hummingbird/clearwing moths have started to investigate what’s on offer, and dragonflies seem to have discovered the aliveness of our yard, resting on stones in the sunshine, warming their wings.

It is a remarkable journey, tending a garden from a blank canvas to the stunning abundance that we see now. And each year, I make more plans for what’s next, what to add, where to extend, and what new plants to bring in to attract more native wildlife because, after all, that’s the whole point.